By Fungayi Sox

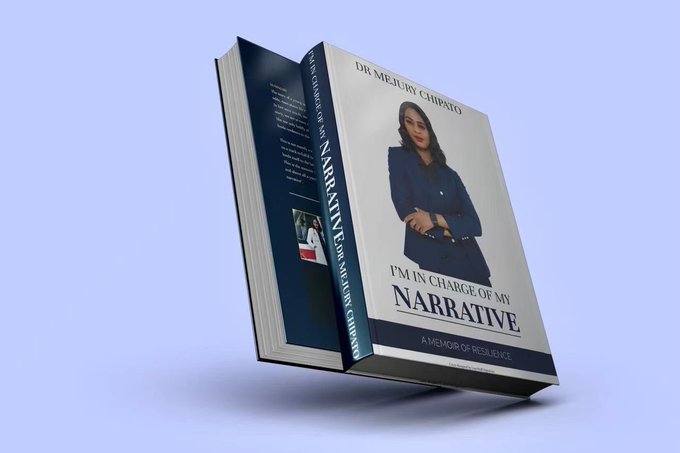

It is Kahli Gibran who once remarked: “Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls, the most massive characters that are seared with scars.” This quote perfectly strikes a chord with Mejury Chipato’s latest book — I’m In Charge of My Narrative — a story which in my view is one of “turning lemon into lemonade”.

Chipato is a Zimbabwean medical doctor based in China. She holds degrees in Medicine, Surgery and Microbiology and is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in Microbiology.

Upon getting hold of her book a week ago, what immediately caught my attention was of course the title I’m In Charge of My Narrative which resonates perfectly with the name of this column Building Narratives, which captures stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

“Out of the rural came something refined.

Out of the Narrative, came something poignant”– (pp.29)

In her debut book I’m In Charge of My Narrative, Chipato capture’s her journey from the deep rural heart of Gutu in Masvingo Province, to Mbare after which she leaves the country to become a highly successful medical doctor, businesswoman, entrepreneur and philanthropist.

The book has been endorsed by leaders in business, church and politics with businessman Phillip Chiyangwa stating that: “Throughout her narrative Chipato shows that yesterday is gone and so it can only guide and strengthen us… I am also from a humble beginning in Chegutu, but here I am among the richest people in Zimbabwe. I can easily relate to Chipato’s touching narrative”.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

One of her unique styles in writing is how she captures her struggles in Gutu in a lighter sense which in most instances, instead of sympathising with her predicament, leaves one in stitches. For instance in chapter one Chipato narrates how as a child she feared going to the toilet because of ghost stories which village people used to murmur about.

“I remember one night I pooped on myself after having a heavy meal of Bambara groundnuts (mutakura wenyimo). I couldn’t go outside to answer to the call of nature since it was too dark, and no one wanted to escort me outside. The following day, my friends and siblings made fun of me, and this story never left their lips”– (pp.35)

She also reveals how living in the rural areas taught her not to be selective when it came to food as she ate everything from dried leaves (mufushwa) pumpkin leaves (muboora) and other related traditional foods.

In an insightful reflection, Chipato also narrates how she nearly drowned in a well before she she was rescued by her sister.

“From nowhere my sister appeared and pulled me out of the water when I was almost drowning. Her timing was impeccable, a delay of even two more minutes would have rendered me history and there would certainly have been no story to write about today”– (pp.39)

As she relocates to Mbare, Harare’s oldest high-density suburb, Chipato seems to pose a pertinent metaphorical question “Can anything good come out of Mbare?”, an issue she later on addresses towards the end of the book.

Her greatest strength as an author is her ability to paint the squalid living conditions in Mbare and how government’s Operation Murambatsvina left them homeless and had to seek refuge at a relative’s place and how her family ended up living in a one roomed house.

“It was a one roomed house, and the toilets were public. We quickly moved in, the five of us, alongside one more relative who had equally lost his home to Operation Murambatsvina which led to the eight of us living in one room. To attempt to fully describe the nuance of living in high density populated flats would necessitate the writing of another book. All I can say is that the government needs to intervene urgently because the life that’s being lived there is not appropriate and conducive to raise the next generation of our nation” – (pp.54).

It is against this background that she was forced to turn up early at school despite her lessons starting off in the afternoon in an attempt to escape their family overpopulated one room.

For the greater part of the book, Chipato chronicles struggles she encountered growing up and how determination, hard work, resilience and hope eventually rescues her from the jaws of poverty and sets her on a trajectory to success.

Given this background of encountering struggles at an early age, Chipato shares four important nuggets.

Firstly, it is in light of these struggles that she started making declarations of the kind of life and career she wanted up until she became a medical doctor. The lesson she shares here is that of the power of affirmations or declarations on how one can transform dreams into reality.

I swore to myself that I would work hard till I changed the narrative of my life and that of my family – (pp.57)

Secondly, she challenges those from poor background to be resilient and never to give up on their dreams.

Thirdly she cites goal setting as an essential stepping stone to greater heights.

Finally, she emphasises the importance of cultivating personal relationships and networks as a crucial ingredient for success.

- Fungayi Sox is the managing consultant at TisuMazwi — a communications consultancy firm that facilitates book project management including writing and publishing, content development and marketing, digital media and personal development coaching. He writes in his personal capacity and can be contacted on 0776 030 949 or connect him on Linkedin on Fungayi Antony Sox.